Yesterday at dinner me and my sister had conversation about how digital photos are made, and what do all these strange definitions mean. Then I remembered the time when I was struggling to understand all these concepts. It took me some time to wrap my head around them.

I think many beginner photographers are still struggling with them. So I’d like to share what I have learned and understood in the way that is clear to me, and hopefully will be clear to you.

Let’s start with the initial image that comes out of the camera – what does it mean that camera produces, let’s say, 10 Mega pixel image?

Ok, before answering this question let’s explain what a “pixel” is. Pixel is a virtual dot. Yes, a virtual one – it doesn’t have dimensions of its own. Let’s just leave it at that for now and I’ll explain down the road when pixel gets it’s physical dimensions. Now imagine a rectangle shape filled with dots. On its long side it has 3648 dots and on its short side it has 2736 dots. So the total number of dots would be 3648*2736=9,980,928 – it is almost 10 million dots or in other words 10 Mega pixels.

All digital images are “composed” from pixels (dots). Each pixel has its own set of values such as color, brightness, saturation etc.

So when we say that camera produces 10 Mega pixel images, it means that for each image camera provides this set of values for ten million pixels, all these numbers being put into a single JPEG or RAW (or any other format) file.

When you load this image on your computer’s display all these values are translated into actual color, intensity, etc. and together form the captured photo. Remember I said that pixel has no dimensions? As long as it “sits” in the JPEG or RAW file it doesn’t, but as soon as the file is displayed on the display, pixel receives its physical dimensions depending on DPI, on which I’ll explain next.

Let’s stay with the 10 Megapixel photo for now, and try to understand the DPI. DPI stands for Dots Per Inch. So basically if we have, for example, 10 DPI resolution then it means that for each square inch of image we have 100 pixels (10 by 10) with information regarding their color, intensity, etc. And these 100 pixels are taking the whole square inch, so they each pixel has certain size. And if we have 20 DPI resolution then we have 20×20 pixels per square inch (400 in total), therefore each pixel is smaller, and the result is better sharpness of the image.

You might get confused a little bit at this point – DPI stands for DOTS per inch but I’m talking about pixels. Here’s the thing – when a dot displayed on the computer screen, it is called a pixel, and when this same dot is printed on the paper, it is called a dot. Sometimes the abbreviation PPI (Pixels Per Inch) is used for computers but I’ll mostly stick to DPI.

Now let’s talk some real numbers

If you are displaying your images on computer display, then you don’t need resolution higher than 72 DPI because of physical limitations of the display (the smallest dot that display can show is of certain size, so physically there can be no more than 72 pixels per inch displayed on computer screen). If you’ll save your images in a higher resolution than 72 DPI and only look at them on your computer, you will just waste your storage space because the bigger your DPI, the more space the photo will take on your hard drive provided its physical dimensions stay the same.

If you want to print your photos, then resolutions of 240 DPI or even better 300 DPI are appropriate. This is due to the fact that printer can print much smaller dots than computer screen can show. If you’ll use a much lower resolution for printing, then instead of nice photo with sharp detail and smooth color transitions you’ll see image comprised of colored squares because your digital file will contain inefficient amount of data.

Let’s go back to the digital image produced by a 10 Megapixel camera. As we already said, this image contains information about 10 million dots/pixels. That’s it, not less and not more. Now when you want to print this digital image, these 10 million dots are your limit, and it is for you to decide how to use them.

For example if you want to print at resolution of 300 DPI (to remind you DPI stands for Dots Per Inch) then you are limited to picture size of 12.16×9.12 inches (30.89×23.16 centimetres). How did I get these numbers? Easy: remember that we said that a 10 Megapixel image has the following dimensions 3648×2736? Now if you divide 3648 by 300 (your desired resolution), you’ll get 12.16 inches for the long side of the printed photograph, and similarly divide 2736 by 300 to get 9.12 inches for the short side. Don’t forget that it is the maximum size for resolution of 300 DPI. You can always print smaller sizes. In that case not all the information contained in the file will be used for printing.

After understanding how the Megapixel count and the resolution (DPI) are affecting the size of the printed image, it is clear that for any given digital image (in our example it is an image from a 10 Megapixel camera) the lower your desired resolution, the larger the printed photo can be.

For most of the printers you don’t need to go above 300 DPI because of the physical limitations of the printer – it simply can’t print more than 300 dots per inch, but when would you like to decrease the printed resolution? I can give one most common example here – printing large posters or ads that will be viewed from long distance. If you look closely at big advertisement signboards with photos, you’ll see that their resolution is very low and you can distinguish between printed dots when looking from close distance, but when looking from farther distances it looks like a good photograph.

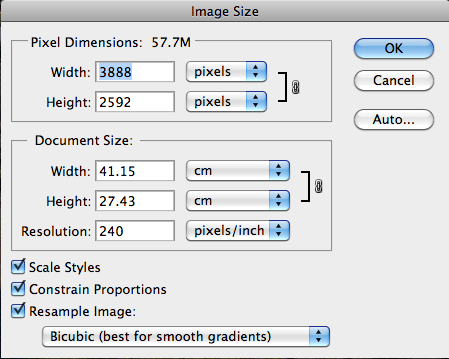

The last thing that I’d like to discuss is the dialog box in Photoshop named “Image Size” because it illustrates perfectly all the concepts I wrote about. In order to get to this dialog box, in Photoshop go to the “Image” menu and from there choose “Image Size”. Then the following window will open:

Of course, the numbers shown are depended on the currently opened image. The numbers that you see in the screenshot above are from 10.1 Megapixel image, but you can play with any photo that you’ve got. As you can see there are three sections in this window:

1. Pixel Dimensions

2. Document Size

3. Check boxes

(For the sake of this exercise, make sure that the “constrain proportions” check box is checked – we want the image to keep its original proportions)

The first two sections are interconnected, which means that if you change numbers in one section, numbers in the other section are also changing.

Lets start with the “Document Size” section, and change the Resolution to a higher number. You’ll see that “Pixel Dimensions” are also changing to higher numbers, and it makes perfect sense – if you want to have more pixels per inch, the total pixel width and height of your image will increase provided that physical dimensions of the photo stay the same. Now change the Width in the “Document Size” section to a lower number. The Height in the “Document Size” section will also change to a lower number because we are constraining our proportions, and more importantly, the Height and Width in the “Pixel Dimensions” section will also change to a lower numbers. Let’s explain that: we kept the resolution intact, but we want the physical width and length of the image to be smaller, which means we want less inches (or centimeters) but with the same 240 Pixels Per Inch, therefore we have less total pixels in our image. Now if we go over to the “Pixel Dimensions” section and change Width (and Height will change correspondingly due to constraining proportions) there to a larger number, then Width and Height in the “Document Size” section will also change to larger numbers. I hope that by now you gained sufficient understanding to explain this change by yourself.

There is one important thing to remember when changing dimensions of your photo in Photoshop – if you try to save the image larger than its original size, Photoshop will use mathematical algorithms to artificially add the additional pixels to enlarge your photo, which won’t always look smooth and natural.

That’s it. It is pretty easy when you take some time to understand the concepts. I hope that if you didn’t fully understand the discussed concepts before, you understand them now, and if not, feel free to leave me your questions in the comments section.

To wrap things up I’ll present some key points to think of when dealing with digital photographs

-

When saving photo for only web usage save it at resolution of 72 PPI

-

When saving photo for printing save it at resolutions of 240 or 300 DPI

-

When saving photo for web or for printing know the size of the photo that you want and save it at that size. This way you won’t waste storage space on your computer.

As always any comments are highly appreciated, and

Remember, you only have to enter your name to leave a comment!

Till the next time,

Cheers!

Greg.

Greg, I wonder what was a trigger for writing a post about pixels.

It’s a very busy post for a rather simple subject…

Stas, I happen to know your background. In addition to having a second degree in electronic engineering, you also have some published academic work related to computer graphics.

Of course this subject is simple for you! But take a step back and think of other people, photography hobbyists who are, let’s say cooks, or doctors – do you think this subject is as easy for them as it is for you?

This blog the way as I see it, is telling a story of you transforming from an amateur photographer to a professional one. The plot is usually a linear one – each time you discover a new technique and new insights and you share them with your viewers. You get postbacks, you improve your methods and you continue conquering the photography world. Here you tell a story that belongs to a very past of your path. The post is well written with many details, but I think it’s too busy in details for beginners. Well, maybe I’m wrong on that one.

Stas

Well, the plot doesn’t necessarily has to be strictly linear 🙂 it is not that I planned all my blog posts in advance. I just discussed this issue with my sister, and realized that many beginners may be struggling with these concepts, therefore I decided to share my knowledge on the subject.

About the details, maybe you’re right on this one, and I’d be happy to hear more feedback from other readers.

Thank you Greg – I am not a beginner, but, it certainly makes better sense to me now, then when I was. It was also very helpful, for when I publish photos on the web (to save space) or print them. I like the details, thank you! I will be adding this to my information folder for future reference. I don’t recall my graphics instructor giving this much information on the subject, he just implied that the numbers are all I needed, not the why or how.

You welcome Rona. I think when you understand the why and the how it moves you forward in anything that you do.

Thank you very much for this post. I was researching this very thing today as I am looking into making very large prints of my work for my office. I wasn’t sure if my images were going to create crisp prints. After reading this I know!

Thank you for this article Greg, I was looking for this exact information just a few days ago and I couldn’t find anything as well written and simply explained. Cheers!

Dana, Kara, thank you. I am glad that you found this information useful

Greg thanks for the awesome article. I have a bit confusion about the pixel. If the pixel’s size can vary then what is the exact unit used in the monitor?

I understand your confusion. The thing is that the term “resolution” when used for monitors only describes the number of pixels in each dimension (for example 1600×1200). From this number you can’t determine the size of individual pixel, which is different for each monitor. For example MacBook Pros with 15′ displays up until mid 2012 had pixel density of 110 pixels per inch, while the new MacBook Pro with same 15′ but retina display has pixel density of 220 pixels per inch (twice as much pixels “inside” the same sized display). You can however determine the size of the pixel if you take maximum resolution of the monitor and its size (e.g. 15′, 17′ etc.).

I meant if a single pixel does not fill a specific area in my monitor (as it’s size might change!) then it is difficult to absorb the whole idea. Then what is a pixel made of? Is it possible to divide a single pixel (which is enlarged) into small pieces?

Oops! Your reply came up when I posted my second question! you have answered me already. Thanks a lot:)

Hi Guys,

If you want a decent picture for any practicable use, forget the formulas; simply own nothing smaller than a 14.0 megapixel digital camera and be sure it is set at “highest quality”.

Then when working in ANY printer program, especially Adobe programs, for printing/pulishing, choose minimum setting of 300 dpi — and if you want class and 8 x 10 or above, set printing at 600 dpi and “highest quality” — wherever these options are available.

NOTE: El-Cheapo computers use “ppi” — which stands for “pitiably poor image” (my humble opinion) — just don’t go there.

I’ve only been shooting cameras for a living and publishing since 1965, printing digitally since 1985, and making books since 1998 — but I do feel I have steered you quickly to safe “markers”

If you really want “the best,” go buy a Nikon latest model for about $355 — and stay away from the little digital darlings.

Photography can be pure joy.

Good clicking!

Mike,

I appreciate your expertise, but have to disagree with you. I have a Canon 40D DSLR which has 10.1 Megapixels, and I got perfectly fine A4 prints from it.

I also have experience with printing at 240dpi, which also looks perfect to me. So I don’t understand why you go up to 600 dpi, and urge people to get 14.0 megapixel cameras and higher.

Please elaborate on that if you can.

thank you very much, nice article.

As an industrial photographer in India, I have to take prints of some of the photographs that I take. Armed with a 12 MP Canon 450D camera, I have printed prints large enough for 30″ x 20″ canvas prints.

Hi, this is a nice and useful article, i’ve a doubt: as u said my laptop screen resolution is 1 MP (1366*768), when i opened an image of 5MP it stretched to screen with full clarity, but when i printed the same image on photopaper it was blurred and and photo paper size is exactly equal to the physical size of my laptop screen. how is this possible?

Hi there. I am not sure what laptop do you have. But for example Macbook Air 11″ has the same resolution. But pay attention to its PPI (points per inch), which is 135. In printing the corresponding name would be DPI (dots per inch). For the print to look sharp you need to print at at least 200 DPI. It basically means that printed ‘dots’ are smaller than ‘points’ on the screen. So if, in your digital image file, you only have enough data for 135 dots per inch (for the size that you printed it at), then, when you print this file it will be blurry.

However it would still appear sharp enough when you look at it on your display.

Hi Greg,

Its a really useful and valuable post for an amateur photographer like me.I use Nikon D5100 which is having 16.2 mega pixels and I’m looking for a larger print.So will the 300 dpi suffice or I can go for a larger dpi? The print will be a little bit larger than the regular ones.

Thanks in advance.

Hi, Greg, I’m just starting out in digital photography. I appreciate the article, numbers are comforting, and knowing how something works makes the whole thing more enjoyable. I can’t wait to read more.

I have two cameras, both set to the highest resolution possible for each. One is an inexpensive Canon Powershot A590 with advertised 8 Megapixel capability the other a Canon EOS Rebel T3 with advertised 12.2 Megapixel capability. Raw images from the camera to my PC show the Powershot images are 180 dpi and the T3 images are 72 dpi. There seems to be no way (that I’ve found) to increase the resolution (dpi) of the T3 to get anything greater than 72 dpi. For paper printing and web use that’s fine but for print publication, image items are noticeably fuzzier. Is there a “fix” for the T3 or would moving up to a Nikon D7100 resolve the issue?

It was helpful

Great info; thanks for explaining it in an easy-to-follow way

Best explanation I’ve found on this topic thank you.

Thanks Terry, I’m glad you found it helpful!

Can we just save images to storage at 72 dpi, and then when we print from Photoshop enlarge the DPI to 300 dpi and “resample”? Then – without saving to storage – just print the 300 dpi image that is now loaded into Photoshop?

Simple and elegantly explained. Thanks Greg. I wish lot of things in internet are explained this way. 🙂

Thank you Arun!

It really doesn’t matter at what dpi you save the image. What matters is the actual dimensions of the image. For example if the image is 900×800 pixels and you want to print it at 300 dpi, it will be a very small image on paper. But if the image is 3000×2000 pixels then you can print it fairly large in 300dpi. Also the image will take the same amount of bytes on your HDD whether you save it at 72 or 300 dpi as long as it is the same resolution (eg. 900×800 or 3000×2000)

So when we scan a photo to create a digital archive image, what would be your recommendations for the scanner settings, to give maximum flexibility on future printing of the image?

Well, ‘maximum’ is a relative concept 🙂

You could always just set the best quality that your scanner can provide. I would suggest scanning at 300dpi for good print quality. However I also must say that I know of professional printing studios that require only 240dpi and prints come out perfect.

Thanks for nicely explained article Greg. May I know that when receive any snap taken by a mobile of resolution of 13 MP and save the same on mobile/lap top for further printing the same, does its resolution deters?

Thanks – great article. I came here searching for “DPI vs Megapixel” on Google.

Thank you for the explanation. I have been trying to decide between a photo scanner that scanned in 300 or 600 dpi and one that scanned up to 22 mega pixel and was confused about what the difference was. I plan to scan a lot of old photos for our family history. Again, thanks!